The maritime security environment in the Red Sea as of January 2026 represents a complex mixture of asymmetric warfare, regional power realignments, and structural shifts in global logistics. Following more than two years of sustained disruption started by the Houthi movement (Ansar Allah) the theater has transitioned from a localized conflict into a primary driver of global supply chain re-engineering. [1] For US commercial shipping, the start of 2026 is characterized by a precarious stability: while a 100-day hiatus in kinetic attacks has fostered tentative test transits by major carriers, the underlying threat to US-flagged and US-linked vessels remains substantial, governed by sophisticated weaponry and shifting geopolitical alliances. [2]

The Evolution of the Asymmetric Threat Landscape

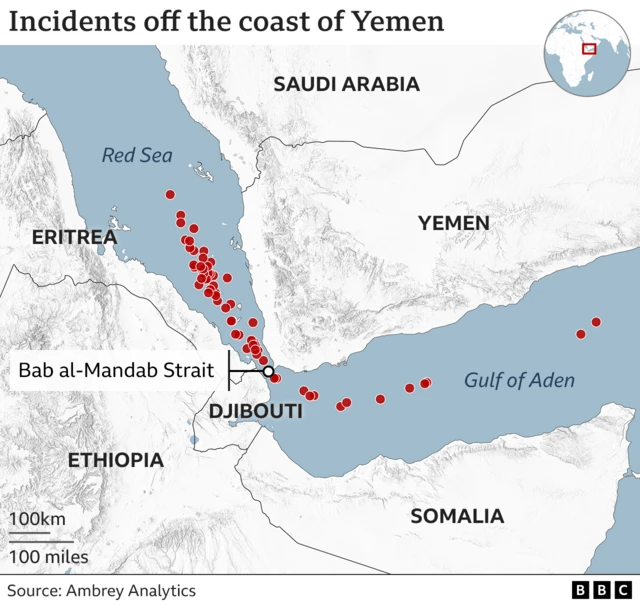

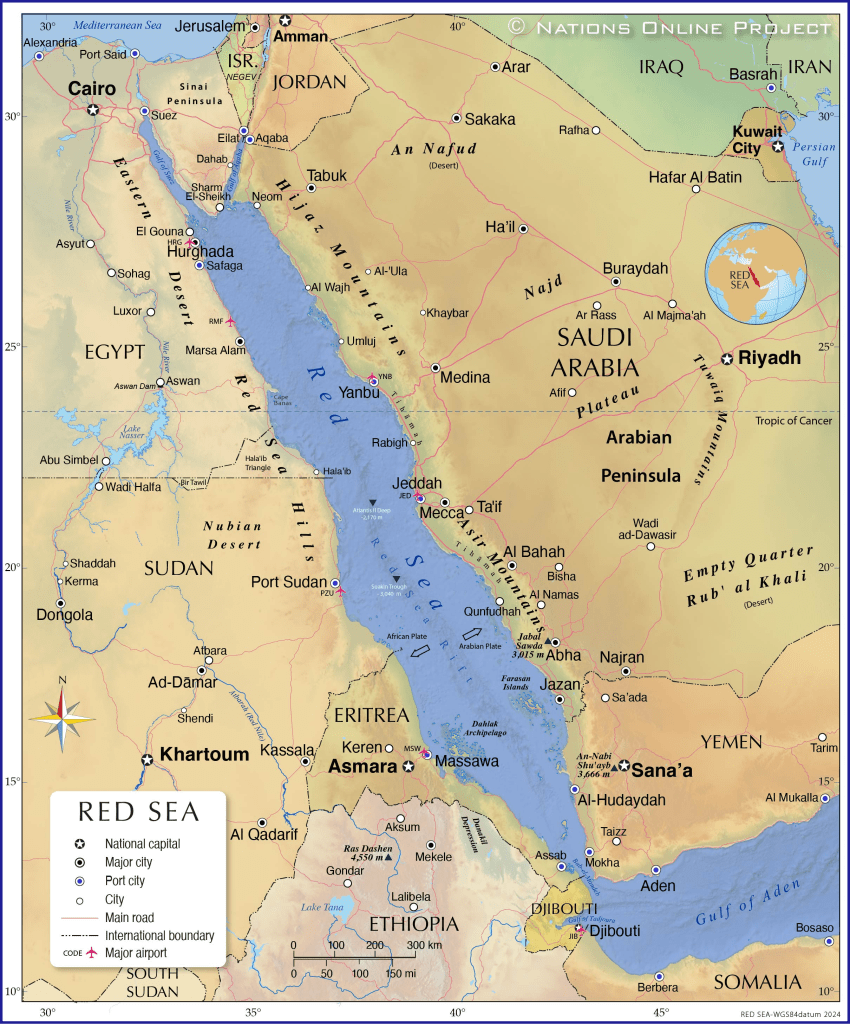

The Houthi movement has fundamentally altered the paradigm of maritime security by showing that a non-state actor can exert strategic influence over global trade routes through low-cost, high-impact technology. Since the escalation of attacks in late-2023, the southern Red Sea, the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, and the Gulf of Aden have become contested areas where traditional naval deterrence has seen significant limitations.

Kinetic Capabilities and Tactical Sophistication

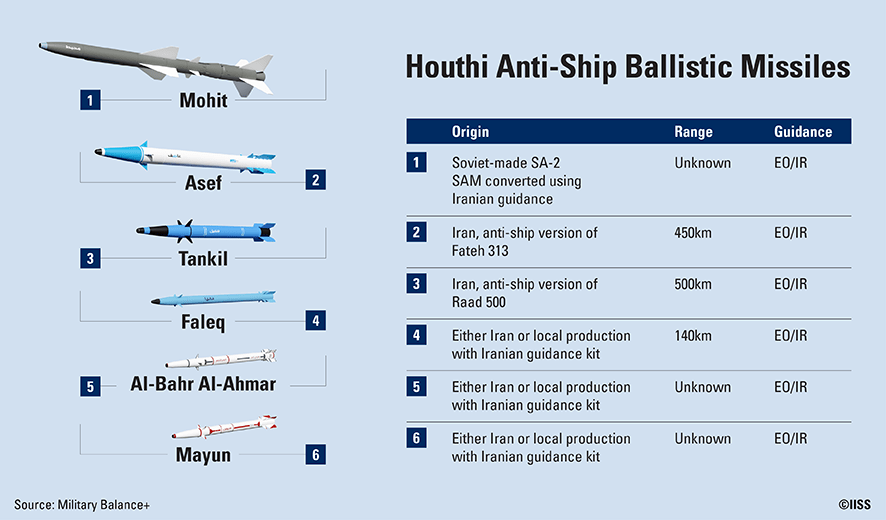

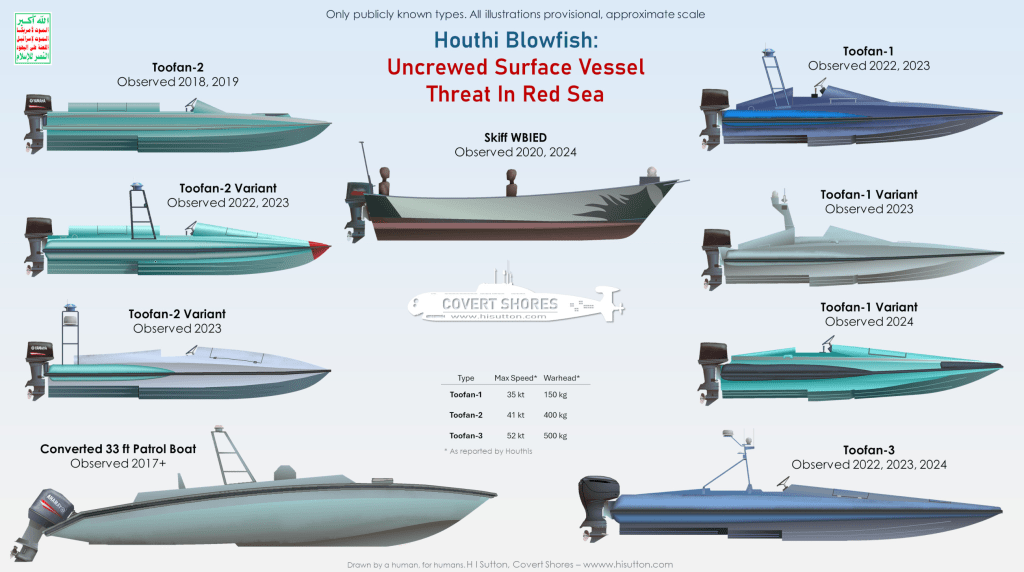

As of January 2026, the Houthis have executed over 120 attacks on commercial vessels. These operations use a diverse arsenal including anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), cruise missiles, one-way attack unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and unmanned surface vehicles (USVs).[4]

A critical development in mid-2025 was the Houthi-announced maritime blockage of Israel, which expanded the targeting criteria to include any vessel within a company fleet if any other vessel in that fleet had called at an Israeli port.

The tactical evolution culminated in July 2025 with the successful sinking of the bulk carriers Magic Seas and Eternity C. These sinkings were particularly significant as they occurred in the absence of rapid-response naval presence, emboldening the Houthis to demonstrate their capability for textbook escalation. [5] The weapons used in these attacks included electro-optically guided Asef ASBMs and anti-ship variants of the Qasim missile, showing a level of precision previously associated only with nation-state militaries.

Current Security Status: The 100-Day Hiatus

The beginning of 2026 has been marked by a notable pause in kinetic activity. The last confirmed Houthi attack ona merchant vessel occurred on 29 September 2025, involving the Minervagracht. This hiatus is mostly attributed to an ongoing, albeit fragile, ceasefire agreement and a monitoring period by Houthi forces. [6] However, the Joint Maritime Information Centre (MIC) and other maritime authorities warn that this pause is highly contingent on the stability of regional peace pacts; a collapse in the Gaza ceasefire would very likely trigger and immediate return to Houthi attacks on US, UK, and Israeli-affiliated interests.

| Maritime Security Incident Summary: Jan 2026 Baseline | Details | Source |

| Total Recorded Houthi Attacks (Nov 2023 – Jan 2026) | 120+ | [2] |

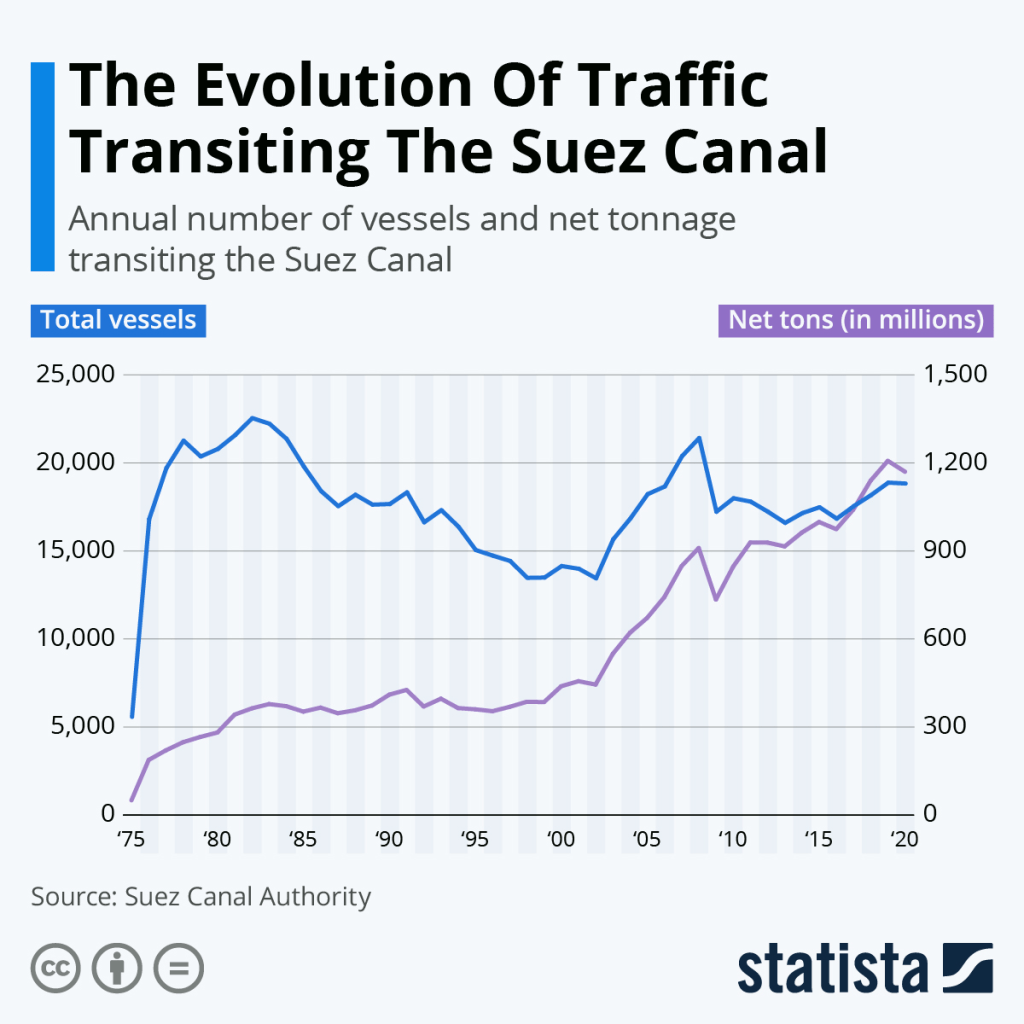

| Current Sueze Canal Transit Reduction | 60% below 2023 levels | [3] |

| Last Kinetic Strike Date | 29 September 2025 | [3] |

| Vessels Sunk Since Conflict Inception | 4 (Rubymar, Tutor, Magic Seas, Eternity C) | [5] |

| Primary Threat Level for US/UK/Israeli Interests | Moderate | [6] |

Electronic Warfare and Hybrid Threats

Beyond kinetic strikes, the Red Sea corridor is plagued by significant electronic interference. In early-January 2026, maritime authorities reported “critical” levels of Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) and AIS interference in the vicinity of Port Sudan and “severe” levels near JeFddah Port. [10] This interference suggests ongoing kinetic activity or electronic countermeasures by state and non-state actors, complicating navigation for commercial vessels and reducing the effectiveness of collision-avoidance systems.

The security vacuum in the region has also facilitated a resurgence of Somali piracy. On 1 January 2026, a Chinese-flagged fishing vessel was hijacked off the coat of Somalia, indicating the Pirate Action Groups (PAGs) are actively monitoring the region’s naval focus on the Houthis to resume ransom-based operations. This collision of piracy and state-level conflict increases the collateral risk for any US-flagged vessel transiting the Gulf of Aden. [11]

Impact on US Commercial Shipping Operations

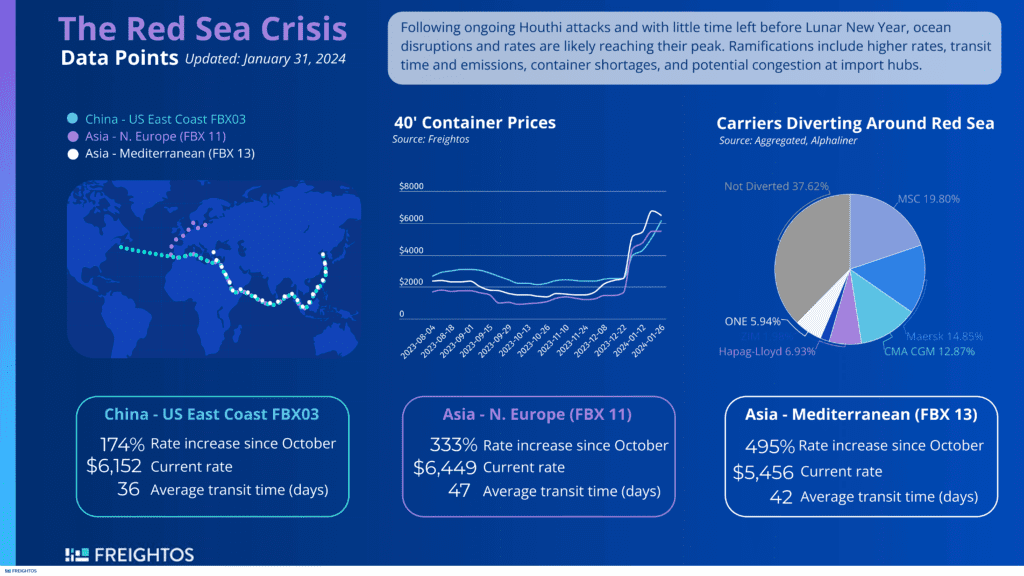

The Red Sea crisis has necessitated a fundamental shift in the operational strategies of US-based shipping firms. The transition from the Suez Canal route to the Cape of Good Hope has moved from an emergency measure to a new normal, with profound implications for costs, lead times, and risk management. [12]

Normalization Attempts and the Maersk Denver Case

The beginning of January 2026 saw a high-profile attempt to normalize US-flagged transits. The Maersk Denver, a US-flagged container vessel, successfully transited the Bab el-Mandeb Strait on 11-12 January. [14] This marked Maersk’s second successful transit since December 2025, and the carrier has indicated a stepwise approach to gradually resuming Red Sea navigation, provided security thresholds continue to be met.

However, the maritime industry remains divided. While Maersk and CMA CGM have tested the route, the Premier Alliance has announced that its network for the first half of 2026 will continue to utilize the Cape of Good Hope route. [15] The reluctance of the broader market to return is reflected in the 60% deficit in Sueze Canal traffic compared to early 2023.

Economic and Supply Chain Macro-Dynamics

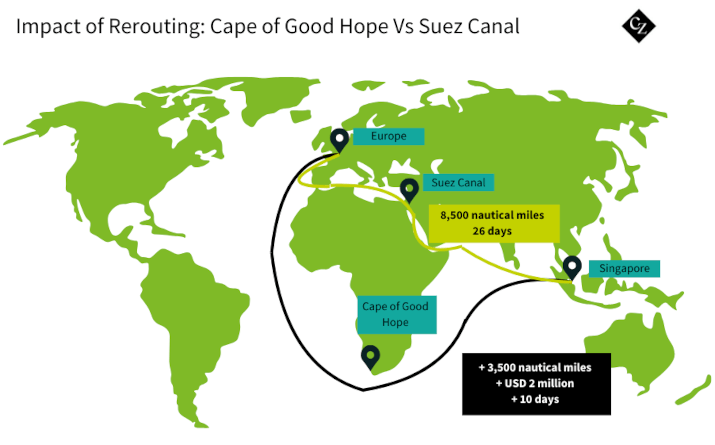

For US shippers, the Cape of Good Hope detour adds approximately 3,500 nautical miles to voyages, increasing transit times by 8 to 17 days. This extended journey has substantial financial consequences:

- Operational costs: Rerouting can add between $2 million and 4$ million USD per voyage in fuel and crew expenses. [17]

- Freight rates: Freight rates remain 25% to 35% above pre-crisis benchmarks as of Jan. 2026.

- Insurance: War risk insurance premiums for Red Sea transits have surged to between $150,000 and $500,000 USD per voyage, making the route economically prohibitive for many carriers.

| Economic Variable | Impact on US East Coast Imports (2026) | Source |

| Additional Transit Time | 10-17 days | [2] |

| Capacity Absorption | 6%-9% of global fleet | [12] |

| Average Additional Cost per TEU | $200 -$400 | [17] |

| Inventory Carrying Cost Increase | 15%-25% due to transit delays | [17] |

A critical risk identified in Q1 2026 is the double wave of arrivals. As some carriers return to the Sueze route while others remain on the Cape route, vessels may arrive at US East Coast and European ports simultaneously. This phenomenon is expected to cause significant port congestion and trigger inland bottlenecks for trucking and rail for several months.

US Port and Regional Considerations

Specific US logistics nodes are feeling the strain of these reroutes. For example, construction delays at Houston’s Bayport terminal have forced the MECL service to shift to Barbours Cut for the first eight weeks of 2026, complicating capacity management during the anticipated pre-Chinese New Year cargo surge. [21] Furthermore, US import volumes from China fell by over 20% in early 2025 as shippers sought more reliable West Coast routings, though East Coast volumes are expected to see a seasonal uptick in early 2026.

Institutional and Regional Security Realignments

The international community’s response to the Red Sea crisis has entered a new phase in 2026, characterized by a transition in US-led naval missions and the emergence of regional security blocs.

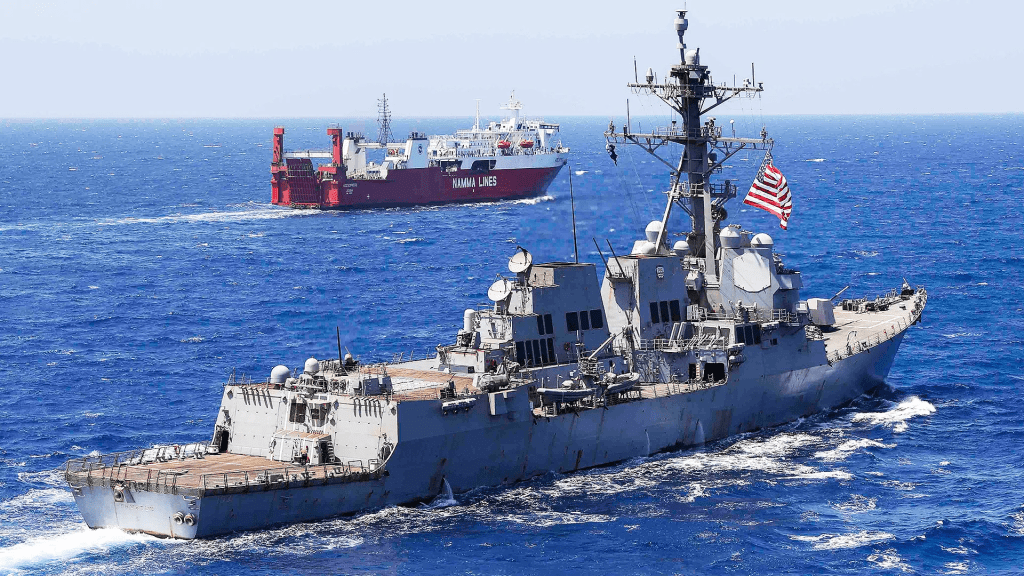

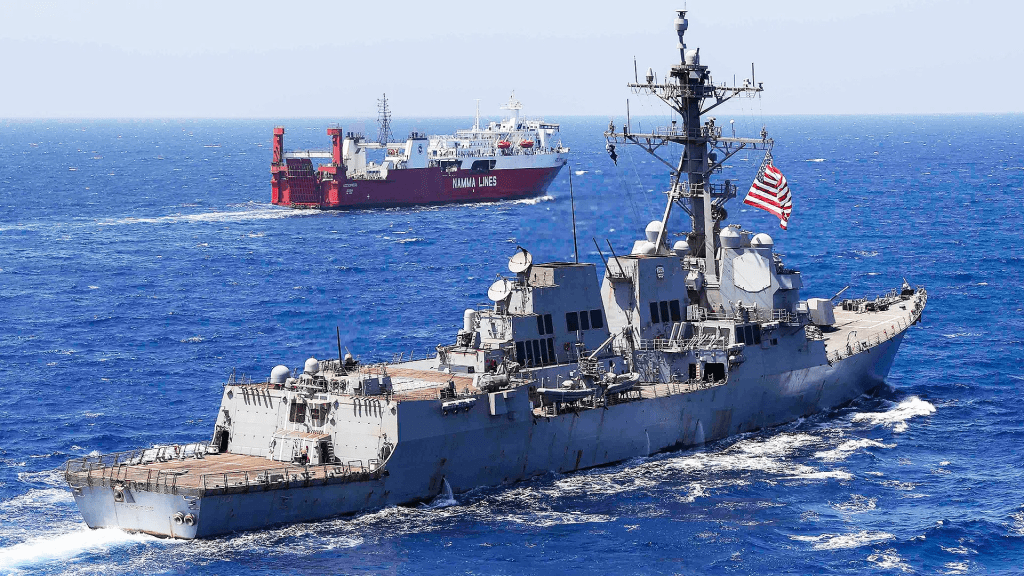

Operation Prosperity Guardian (OPG) and DESRON 50

Operation Prosperity Guardian, the multinational maritime security initiative launched in December 2023, remains active but has undergone organizational shifts. In February 2025, responsibility for the mission was transferred from Combined Task Force 153 to Destroyer Squadron (DESRON) 50, a surface warfare task force under U.S. Naval Forces Central Command. [23] DESRON 50 continues to lead the highway patrol mission in the Red Sea, providing persistent defensive presence and coordinating with industry partners through the JMIC.

Despit OPG’s tactical brilliance (including the first combat use of Standard Missile 3 for ballistic missile defense) critics argue it has been a strategic failure in its primary goal of restoring merchant confidence and pre-conflict shipping volumes. [25] The disparity between the high cost of naval interceptors and the low cost of Houthi drones continues to challenge the sustainability of the current defensive posture.

The “Red Sea Axis”: A Saudi-Turkey Alignment

A major geopolitical development in January 2026 is the proposed formation of a joint naval task force led by Saudi Arabia and Turkey. [28] This “Red Sea Axis” represents a movement toward regional strategic autonomy, looking to fill the perceived vacuum in Western-led security frameworks.

- Ankara Meeting (7 January 2026): High-level naval delegations from Turkey and Saudi Arabia met to establish mechanisms for joint exercises, planning integration, and operational compatibility.

- Strategic Logic: The task force looks to incorporate littoral states like Egypt, Djibouti, Somalia, and Sudan to confront revisionist actors and protect important maritime commerce.

- Technological Enabler: Turkey’s “Blue Homeland” doctrine and its export of Bayraktar Akinci UCAVs provide the technical backbone for this coalition, allowing for 24-hour continuous surveillance over the Bab el-Mandeb independent of US assets.

EUNAVFOR Aspides

The European Union has extended its maritime security operation, EUNAVFOR Aspides, until 28 February 2026. [29] Unlike US-led missions, Aspides maintains a strictly defensive mandate, focused on escorting vessels and intercepting threats without conducting strikes on Houthi land-based assets. While this role is crucial, the mission remains under-resources, with only three to four naval units typically to cover the vast high-risk area.

Defensive Technologies and Onboard Protocols for 2026

As of 2026, the maritime industry has adopted a range of advanced defensive measures and technological countermeasures to mitigate the risks of asymmetric attack.

Counter-UAS (C-UAS) and Directed Energy Weapons (DEW)

The US Navy is accelerating the deployment of non-kinetic defense systems. Project METEOR, a high-powered microwave (HPM) prototype, is scheduled for shipboard testing in 2026. [30] This system is built to defeat cheap UAVs and anti-ship ballistic missiles by disabling their electronic components with microwave energy, providing a low-cost-per-shot alternative to million-dollar missiles.

Internationally, the Greek-developed Centaur C-UAS system has proven highly effective during its deployment on Hellenic Navy Frigates. [31] The Centaur system uses passive receivers to detect drones at long distances and targeted jamming to neutralize them without using kinetic munitions. These developments are critical for commercial operators, as traditional land-based C-UAS systems often fail in the harsh, high-motion maritime environment. [32]

Official Maritime Security Guidance (MARAD)

The US Maritime Administration (MARAD) maintains active advisories for all US-flagged vessels operating in high-risk waters. Advisory 2025-012, effective 26 March 2026, outlines the following critical protocols:

- AIS suppression: US-flagged vessels are strongly advised to turn off their AIS transponders when transiting the southern Red Sea and Bab el-Mandeb, as the Houthis use AIS data for accurate targeting.

- Electronic signature reduction: Crews are advised to secure Wi-Fi routers and minimize all electronic signals that could be used for localization.

- Armed security details: While the use of private maritime security companies is at the master’s discretion, they have proven effective in deterring boardings and small-boat approaches when combined with evasive maneuvering.

- Houthi deceptive communications: Vessels should ignore VHF hails or emails from “Yemeni authorities” instructing them to divert course or activate AIS, as these are common tactics to facilitate targeting.

| MARAD Active Advisory (Jan 2026) | Regional Focus | Effective Until |

| 2025-012 | Red Sea, Bab el-Mandeb, Gulf of Aden, Somali Basin | 26 March 2026 |

| 2025-013 | Foreign Adversarial Cyber/Technical Influence | 4 April 2026 |

| 2025-014 | Global Maritime Security Resources | 4 April 2026 |

| 2025-015 | Gulf of Guinea | 13 June 2026 |

Regulatory Changes Effective 1 January 2026

The beginning of 2026 introduced several mandatory international regulations that intersect with the Red Sea security situation, adding new compliance layers for US operators.

Mandatory Container Loss Reporting

Under new amendments to the IMO’s SOLAS and MARPOL conventions, all ships need to immediately report any container lost overboard. [35] This regulation is particularly pertinent given the Red Sea crisis, as the 191% increase in transits around the Cape of Good Hope has exposed vessels to more extreme weather, leading to a significant rise in container losses; 35% of the 2024 global total occurred near South Africa.

STCW Amendments and Seafarer Safety

Amendments to the STCW Code also entered into force on 1 January 2026, mandating basic training for seafarers on preventing and responding to bullying and harassment. While focused on workplace culture, these measure are part of a larger industry push to support seafarer mental health and safety during the prolonged stress of transiting high-risk conflict zones.

Energy Security and Global Macro-Economic Implications

The Red Sea disruption has reshaped the global energy trade, with US energy exports playing a stabilizing role in the face of Middle Eastern volatility.

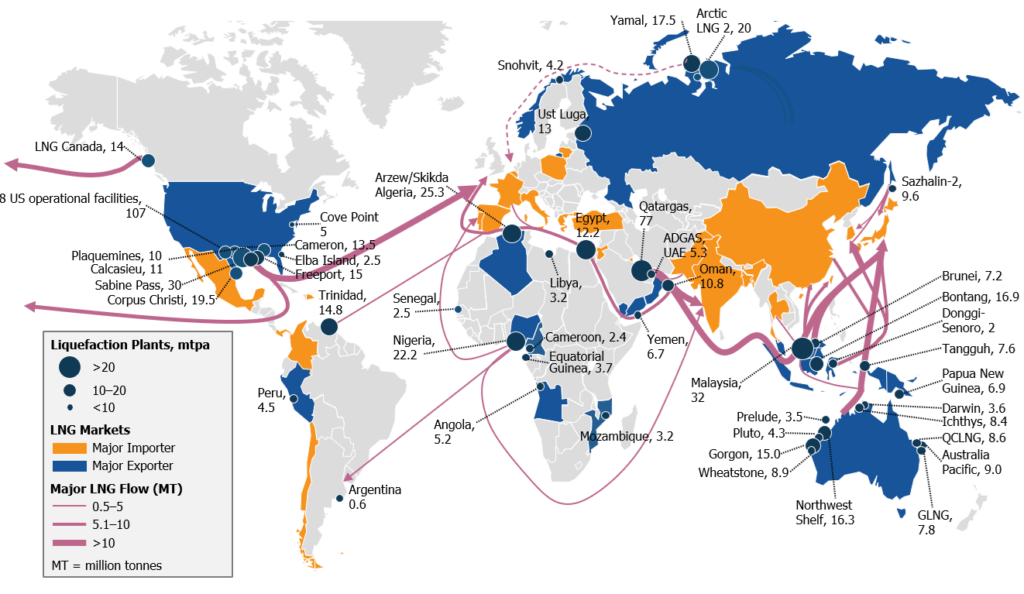

Oil and LNG Flux

The Red Sea is a critical corridor for 8.5 million barrels per day of crude and refined products. [40] The rerouting of tankers around the Cape of Good Hope has increased freight rates for oil by almost 500% since the conflict began. [41] US Gulf Coast complex refiners have emerged as winners in this environment, as European markets have increasingly pulled in US distillates to replace Middle Eastern supplies delayed by the longer Cape route.

The Hormuz Interdependency

A major strategic concern for 2026 is the link between the Red Sea and the Strait of Hormuz. Authorities warn that any major conflict expansion involving Iran could lead to the closure of Hormuz, which handles 20 million barrels of oil per day; nearly 20% of global supply. If both the Red Sea and Hormuz were compromised, the global market would face an unprecedented energy crisis, leaving the US and North America as the primary reliable suppliers of oil and LNG to the world.

Strategic Outlook and Recommendations

As 2026 progresses, the maritime security environment in the Red Sea remains in a state of unstable equilibrium. The hiatus in attacks has allowed for a cautious resumption of transits by carriers like Maersk, but the structural threats posed by Houthi asymmetric capabilities remains unresolves.

Forecast for 2026-2027

Analysts expect that the Red Sea will stay a contested space for the near future. Even if a permanent regional ceasefire is reaches, the Houthi precedent has shown that small forces can successfully disrupt global trade, a lesson likely to be emulated by other non-state actors in chokepoints like the Strait of Malacca or the Strait of Hormuz.

| Operational Forecast 206 | Strategic Implication | Source |

| Phased Return to Suez | Q2/Q3 2026 expected return for larger carrier groups | 12 |

| Freight Rate Normalization | Rates expected to drop as rerouted capacity is released | 12 |

| Persistent Cyber Threats | Increased GNSS/AIS spoofing targeting US vessels | 4 |

| Regional Alliance Growth | Expansion of Saudi-Turkey naval coordination | 28 |

Recommendations for US Commercial Operators

For US shippers and carriers, the 2026 security environment dictates a posture of cautious resilience.

- Risk-based routing: Carriers are advised to maintain a phased approach to Red Sea transits, utilizing test voyages and individual risk assessments for each vessel rather than a wholesale return.

- Adherence to MARAD guidelines: Strict compliance with AIS and electronic signal suppression is important for reducing the targeting footprint of US-flagged vessels.

- Supply-chain diversification: Shippers must continue to buffer lead times and diversify their supplier base to mitigate the impacts of potential chokepoint disruptions elsewhere in the global network.

In summary, the Red Sea in 2026 is no longer a taken-for-granted transit lane but rather a high-risk operational theater. The safety of US commercial shipping now relies on a sophisticated blend of naval protection, regional diplomacy, and advanced onboard security protocols. While the 100-day pause in attacks offers a glimmer of hope for normalization, the strategic volatility of the region ensures that the Cape route will remain a vital, if expensive, component of the global maritime map for the years to come.

Work Cited

[1] https://www.eurasiareview.com/05012026-the-houthis-and-maritime-vulnerability-implications-for-2026-analysis/

[2] https://www.worldshipping.org/red-sea-security

[3] https://www.bimco.org/news-insights/market-analysis/shipping-number-of-the-week/2026/0107-snow/

[4] https://www.maritime.dot.gov/msci/2025-012-red-sea-bab-el-mandeb-strait-gulf-aden-arabian-sea-persian-gulf-and-somali-basin

[5] https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/lethal-attacks-show-strengthened-houthi-control-over-red-sea-transit

[6] https://www.ukmto.org/-/media/ukmto/products/jmic-week-1-dashboard-29-dec-25-04-jan-26.pdf?rev=309f59fca4b847ae8f8fce10313d3b5d

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Prosperity_Guardian

[8] https://www.unmannedsystemstechnology.com/2025/12/official-brochure-launches-for-counter-uas-technology-europe-2026/

[9] https://www.imo.org/en/mediacentre/hottopics/pages/red-sea.aspx

[10] https://www.hellenicshippingnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/20260109_UKMTO_Summary_Report-09Jan26.pdf

[11] https://www.palaemonmaritime.com/post/maritime-security-report-29-december-2025-5-january-2026

[12] https://www.zencargo.com/resources/red-sea-reopening-2026/

[13] https://www.shipuniverse.com/emerging-maritime-supply-chain-disruptions-in-2025-2026/

[14] https://gcaptain.com/maersk-makes-another-voyage-through-red-sea-in-test-of-safety/

[15] https://www.logupdateafrica.com/shipping/red-sea-risks-keep-global-ocean-freight-market-fragile-in-2026-1357736

[16] https://www.seatrade-maritime.com/containers/container-shipping-market-outlook-for-2026-a-red-sea-return-

[17] https://docshipper.com/shipping/red-sea-crisis-update-route-alternatives-cost-impacts/

[18] https://discoveryalert.com.au/shipping-industry-chokepoints-routing-strategies-2026/

[19] https://www.logupdateafrica.com/shipping/red-sea-disruption-shapes-ocean-freight-outlook-for-2026-1357746

[20] https://dredgewire.com/maersk-north-america-market-update-january-2026/

[21] https://www.maersk.com/news/articles/2026/01/08/north-america-market-update-january

[22] https://nrf.com/media-center/press-releases/declining-import-cargo-volume-expected-to-continue-in-2026

[23] https://www.cusnc.navy.mil/Media/News/Display/Article/4052446/destroyer-squadron-50-assumes-operation-prosperity-guardian-mission/

[24] https://www.war.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/article/3624836/ryder-gives-more-detail-on-how-operation-prosperity-guardian-will-work/

[25] https://centerformaritimestrategy.org/publications/the-houthis-operation-prosperity-guardian-and-asymmetric-threats-to-global-commerce/

[26] https://debuglies.com/2025/04/02/operation-prosperity-guardian-a-tactical-triumph-and-strategic-failure-in-safeguarding-red-sea-commerce-lessons-for-global-maritime-security/

[27] https://www.usni.org/USV_Testbed

[28] https://hornreview.org/2026/01/13/order-vs-fragmentation-the-strategic-logic-of-a-saudi-turkey-led-naval-task-force/

[29] https://media.shipco.com/the-eu-extends-red-sea-security-operation-through-2026/

[30] https://news.usni.org/2024/03/27/navy-to-test-microwave-anti-drone-weapon-at-sea-in-2026

[31] https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2024/07/centaur-the-new-combat-proven-c-uas-system-by-hellenic-aerospace-industry/

[32] https://www.smgconferences.com/defence/uk/conference/counter-uas-maritime

[33] https://www.autonomyglobal.co/maritime-defense-services-have-urgent-need-for-counter-uas-technology/

[34] https://www.maritrace.com/blog/industry-associations-release-updated-guidelines-for-commercial-shipping-in-the-red-sea-and-gulf-of

[35] https://www.imo.org/en/mediacentre/pressbriefings/pages/raft-of-shipping-rules-in-force-from-1-january-2026.aspx

[36] https://www.marineinsight.com/shipping-news/mandatory-container-loss-reporting-comes-into-force-under-new-imo-rules/

[37] https://www.mundomaritimo.net/noticias/mandatory-notification-rule-on-containers-lost-at-sea-to-enter-into-force-in-2026

[38] https://gard.no/insights/mandatory-reporting-of-containers-lost-at-sea-starts-1-january-2026/

[39] https://trans.info/en/containers-lost-reported-448177

[40] https://www.woodmac.com/news/opinion/red-sea-crisis-not-for-us-refiners-as-refining-margins-boom/

[41] https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/energysource/the-escalating-conflict-in-the-middle-east-and-its-impact-on-global-energy-security/

[42] https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R45281

[43] https://www.maersk.com/insights/resilience/2024/07/09/effects-of-red-sea-shipping

[44] https://think.ing.com/articles/returning-to-the-red-sea-a-key-event-to-watch-in-container-shipping-for-2026/